The Early History of West Florida

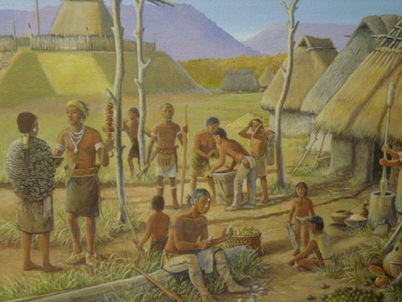

Indigenous People

The history of Florida can be traced back to when the first Native Americans began to inhabit the peninsula as early as 14,000 years ago. The area had been inhabited for thousands of years by indigenous peoples of varying cultures that left behind artifacts and archeological evidence. At the time of first European contact in the early 16th century, Florida was inhabited by an estimated 350,000 people belonging to a number of tribes. The cultures of the Florida panhandle and the north and central Gulf coast of the Florida peninsula were strongly influenced by the Mississippian culture, producing two local variants known as the Pensacola and Apalachee cultures. Mississippian peoples were almost certainly ancestral to the majority of the American Indian nations living in this region in the historic era. The Spanish recorded nearly one hundred names of groups they encountered, ranging from organized political entities such as the Apalachee, with a population of around 50,000, to villages with no known political affiliation. The historic and modern day Native American nations believed to have descended from the overarching Mississippian.Cultures include the Alabama, Apalachee, Caddo, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Guale, Hitchiti, Houma, Kansa, Missouri, Mobilian, Natchez, Osage Nation, Quapaw, Seminole, Tunica-Biloxi, Yamasee, and Yuchi, also known as Euchee.

One example of the impact on the native people by the European settlers is referenced with the tribes of the Timucua who lived in Northeast, North Central Florida, and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in the area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. While alliances and confederacies arose between the chiefdoms from time to time, the Timucua were never organized into a single political unit. The populations of all of these tribes decreased markedly during the period of Spanish control of Florida, mostly due to epidemics of newly introduced infectious diseases, to which the Native Americans had no natural immunity. By 1595, their population was estimated to have been reduced from 200,000 to 50,000 and only thirteen chiefdoms remained. By 1700, the population of the tribe had been reduced to 1000. Warfare against them by the English colonists and native allies completed their extinction as a tribe soon after the turn of the 19th century. The example that impacted the Timucua people occurred across the entire Florida region and affected every tribe in the area.

At the beginning of the 18th century, when the indigenous peoples were already much reduced in populations, tribes from areas to the north of Florida, supplied with arms and occasionally accompanied by white colonists from the Province of Carolina, raided throughout Florida. They burned villages, wounded many of the inhabitants and carried captives back to Charles Towne to be sold into slavery. Most of the villages in Florida were abandoned ,and the survivors sought refuge at St. Augustine or in isolated spots around the state. Many tribes became extinct during this period and by the end of the 18th century. Some of the Apalachee eventually reached Louisiana, where they survived as a distinct group for at least another century. The Spanish evacuated the few surviving members of the Florida tribes to Cuba in 1763 when Spain transferred the territory of Florida to the British Empire following the latter's victory against France in the Seven Years War. In the aftermath, the Seminole, originally an offshoot of the Creek people who absorbed other groups, developed as a distinct tribe in Florida during the 18th century.

One example of the impact on the native people by the European settlers is referenced with the tribes of the Timucua who lived in Northeast, North Central Florida, and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in the area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. While alliances and confederacies arose between the chiefdoms from time to time, the Timucua were never organized into a single political unit. The populations of all of these tribes decreased markedly during the period of Spanish control of Florida, mostly due to epidemics of newly introduced infectious diseases, to which the Native Americans had no natural immunity. By 1595, their population was estimated to have been reduced from 200,000 to 50,000 and only thirteen chiefdoms remained. By 1700, the population of the tribe had been reduced to 1000. Warfare against them by the English colonists and native allies completed their extinction as a tribe soon after the turn of the 19th century. The example that impacted the Timucua people occurred across the entire Florida region and affected every tribe in the area.

At the beginning of the 18th century, when the indigenous peoples were already much reduced in populations, tribes from areas to the north of Florida, supplied with arms and occasionally accompanied by white colonists from the Province of Carolina, raided throughout Florida. They burned villages, wounded many of the inhabitants and carried captives back to Charles Towne to be sold into slavery. Most of the villages in Florida were abandoned ,and the survivors sought refuge at St. Augustine or in isolated spots around the state. Many tribes became extinct during this period and by the end of the 18th century. Some of the Apalachee eventually reached Louisiana, where they survived as a distinct group for at least another century. The Spanish evacuated the few surviving members of the Florida tribes to Cuba in 1763 when Spain transferred the territory of Florida to the British Empire following the latter's victory against France in the Seven Years War. In the aftermath, the Seminole, originally an offshoot of the Creek people who absorbed other groups, developed as a distinct tribe in Florida during the 18th century.

Florida under European Influences

|

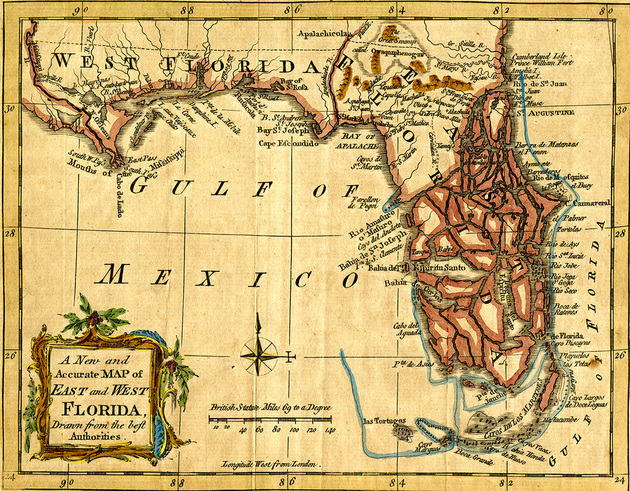

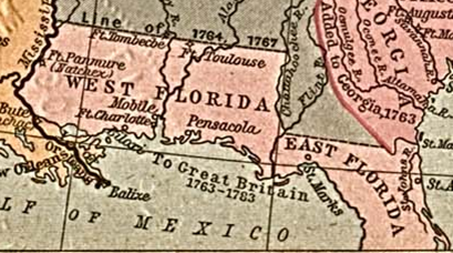

Right - "A Map of the New Governments of East and West Florida " by John Gibson, published in 1763 in The Gentleman's Magazine, London, in relation to the French and Indian War. The original is a copper engraved map. Lower East Florida is depicted as a conglomerate of islands. These islands were occupied by the indigenous tribes of Florida.

|

How West Florida Came to Be

Left - Map of East and West Florida - 1767 British West Florida

West Florida covers half of Mississippi, half of Alabama, some of Louisiana, and the northwestern part of Florida. It originally extended to the Mississippi River.

West Florida was a region on the north shore of the Gulf of Mexico, which underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history.

The late fifteenth-century landfall by Christopher Columbus on the island of Guanahani, in the Bahamas, forced open the gates to a whole new world for the Spanish and other European explorers. America, as it came to be called, became the destination for numerous expeditions and adventures from 1492 onward. Written history of Florida begins with the arrival of Europeans, made in 1513 by Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León.

According to the "500TH Florida Discovery Council Round Table", on March 3, 1513, Ponce de Leon, organized and equipped three ships which began an expedition (with a crew of 200-including women and free blacks), departing from Punta Aguada Puerto Rico. Ponce de León spotted the peninsula on April 2, 1513. According to his chroniclers, he named the region La Florida ("flowery land") because it was then the Easter Season, known in Spanish as Pascua Florida (roughly "Flowery Easter"), and because the vegetation was in bloom. Juan Ponce de León may not have been the first European to reach Florida, however; reportedly, at least one indigenous tribesman whom he encountered in Florida in 1513 spoke Spanish.

Puerto Rico was the historic first gateway to the discovery of Florida, which opened the doors to the advanced settlement of the USA. The influx from Puerto Rico introduced Christianity, cattle, horses, sheep, the Spanish language and more to the lands of La Florida, 107 years before the Pilgrims landed. From the time of recorded first contact, Florida has had many waves of immigration, including French and Spanish settlement during the 16th century, as well as entry of new Native American groups migrating from elsewhere in the South, and free blacks and fugitive slaves, who became known as Black Seminoles.

The western portion of Florida stretched from the Mississippi River in the west to the Flint / Chatahoochee River in the east. Spain made several attempts to conquer and colonize the area, but permanent settlement did not occur until the 17th century, with the establishments of missions to the Apalachee.

Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1519–1571) was a Spanish conquistador of the 16th century who led an ill-fated expedition to the Pensacola area in 1559. On June 11, 1559, de Luna set out from Mexico with 500 soldiers, 1,000 colonists and servants, and 240 horses. Around August 15 of the same year, he sailed into Pensacola Bay, and established an ephemeral colony on the shore soon thereafter that became the first European settlement within the continental boundaries of the United States.The party anchored in Pensacola Bay, which they called "Ochuse", and set up the encampment of Puerto de Santa Maria during the summer of 1559, at the site of the modern Naval Air Station Pensacola. With much of the colony's stores still on the ships, de Luna sent several exploring parties inland to scout the area. They returned after three weeks having found only one Native American settlement. Before they could unload the vessels, a hurricane swept through and destroyed most of the ships and cargo. With the colony in serious danger, most of the men traveled up the Alabama River to the village of Nanipacana (Nanipacna or Ninicapua), which they found abandoned; they renamed the town Santa Cruz and moved in for several months. Back in Mexico, the Viceroy sent two relief ships in November, promising additional aid in the spring.

The relief got the colony through the winter, but the supplies expected in the spring had not arrived by September. De Luna ordered the remainder of his force to march to the large native town of Coca, but the men mutinied. Bloodshed was averted by the settlement's missionaries, but soon after Ángel de Villafañe arrived in Pensacola Bay and offered to take all who wished to leave on an expedition to Cuba and Santa Elena. De Luna relented and agreed to leave, eventually returning to Mexico. The Pensacola settlement disbanded completely within several months of his departure. De Luna was appointed governor of Yucatan in 1563 and remained in that capacity until his death in 1571. The area would remain unsettled by European powers for the next 140 years.

In the late 17th century (1698) the French were seeking to settle near the mouth of the Mississippi River. To defend their holdings here, the Spanish constructed the Fort San Carlos de Austria and laid a foundation for what would become Pensacola. On May 14th, 1719, Governor of French Louisiana, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville arrived with his fleet and a large ground force of Indian warriors, attacked the fort, and took Pensacola for France. The Spanish commander of Pensacola, Metamoras, had not heard that war had been declared between France and Spain, and his garrison was so small that he felt it would be useless to resist so at four o'clock in the afternoon, he surrendered on the conditions that private citizens and property should not be disturbed and the garrison should march out with honors of war and be shipped to Havana in French vessels. Bienville left about sixty men at Pensacola and sailed away. The French, who had established settlements also further west at Mobile and Biloxi, held Pensacola and remained in control for three years. A hurricane drove the French from Pensacola in 1722 and they burned the settlement upon their retreat. The Spanish moved the town from the storm-vulnerable barrier island to the mainland. After years of contention the Perdido River (the modern border between Florida and Alabama) was agreed upon as the boundary between French Louisiana and Spanish Florida.

Florida attracted numerous Africans and African Americans from the southern British colonies in North America who sought freedom from slavery. Once in Florida, the Spanish Crown converted them to Roman Catholicism and gave them freedom. Those freed men settled in a community north of St. Augustine, called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first free black settlement of its kind in what became the United States. Many of those slaves were also welcomed by Creek and Seminole Native Americans, who had established settlements in the region at the invitation of the Spanish government.

In the treaty negotiations concluding the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), France ceded to Britain the part of Louisiana east of the Mississippi River, notably excluding the Île d'Orléans, which includes New Orleans. A separate treaty transferred the rest of Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain in exchange for Cuba, which the British had captured during the war. As a result of these exchanges the British controlled nearly all of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi. Most of the Spanish population left Florida, and its colonial government records were relocated to Havana, Cuba. In 1767, the British moved the northern boundary of West Florida to a line extending from the mouth of the Yazoo River east to the Chattahoochee River (32° 28′north latitude), consisting of approximately the lower third of the present states of Mississippi and Alabama.

The newly acquired territory was too large to govern from one administrative center, and the British divided it into two new colonies separated by the Apalachicola River. British West Florida's government was based in Pensacola, and the colony included the part of formerly Spanish Florida west of the Apalachicola, plus the parts of French Louisiana taken by the British. The British colony of West Florida, with its capital at Pensacola, included all of the Panhandle west of the Apalachicola River, as well as southwestern Alabama, southern Mississippi, and the Florida parishes of modern Louisiana. West Florida included the important cities of Pensacola, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and, disputably, Natchez. In 1763, the British laid out Pensacola's modern street plan. This period included the major introduction of the slave-based cotton plantation economy and new settlement by Protestant Anglo-British-Americans and black slaves. British East Florida, with its capital at Saint Augustine, included the rest of modern Florida, including the eastern part of the Panhandle. It thus comprised all territory between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, with a northern boundary that shifted several times over the subsequent years. Both West and East Florida remained loyal to the British crown during the American Revolution, and served as havens for Tories fleeing from the Thirteen Colonies.Britain tried to develop the Floridas through the importation of immigrants for labor, but this project ultimately failed. Spain invaded West Florida and captured Pensacola in 1781. Spain received both Floridas after Britain's defeat by the American colonies and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, continuing the division into East and West Florida. They offered land grants to anyone who settled in the colonies, and many Americans moved to them. However, the lack of defined boundaries led to a series of border disputes between Spanish West Florida and the fledgling United States known as the West Florida Controversy.

West Florida covers half of Mississippi, half of Alabama, some of Louisiana, and the northwestern part of Florida. It originally extended to the Mississippi River.

West Florida was a region on the north shore of the Gulf of Mexico, which underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history.

The late fifteenth-century landfall by Christopher Columbus on the island of Guanahani, in the Bahamas, forced open the gates to a whole new world for the Spanish and other European explorers. America, as it came to be called, became the destination for numerous expeditions and adventures from 1492 onward. Written history of Florida begins with the arrival of Europeans, made in 1513 by Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León.

According to the "500TH Florida Discovery Council Round Table", on March 3, 1513, Ponce de Leon, organized and equipped three ships which began an expedition (with a crew of 200-including women and free blacks), departing from Punta Aguada Puerto Rico. Ponce de León spotted the peninsula on April 2, 1513. According to his chroniclers, he named the region La Florida ("flowery land") because it was then the Easter Season, known in Spanish as Pascua Florida (roughly "Flowery Easter"), and because the vegetation was in bloom. Juan Ponce de León may not have been the first European to reach Florida, however; reportedly, at least one indigenous tribesman whom he encountered in Florida in 1513 spoke Spanish.

Puerto Rico was the historic first gateway to the discovery of Florida, which opened the doors to the advanced settlement of the USA. The influx from Puerto Rico introduced Christianity, cattle, horses, sheep, the Spanish language and more to the lands of La Florida, 107 years before the Pilgrims landed. From the time of recorded first contact, Florida has had many waves of immigration, including French and Spanish settlement during the 16th century, as well as entry of new Native American groups migrating from elsewhere in the South, and free blacks and fugitive slaves, who became known as Black Seminoles.

The western portion of Florida stretched from the Mississippi River in the west to the Flint / Chatahoochee River in the east. Spain made several attempts to conquer and colonize the area, but permanent settlement did not occur until the 17th century, with the establishments of missions to the Apalachee.

Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1519–1571) was a Spanish conquistador of the 16th century who led an ill-fated expedition to the Pensacola area in 1559. On June 11, 1559, de Luna set out from Mexico with 500 soldiers, 1,000 colonists and servants, and 240 horses. Around August 15 of the same year, he sailed into Pensacola Bay, and established an ephemeral colony on the shore soon thereafter that became the first European settlement within the continental boundaries of the United States.The party anchored in Pensacola Bay, which they called "Ochuse", and set up the encampment of Puerto de Santa Maria during the summer of 1559, at the site of the modern Naval Air Station Pensacola. With much of the colony's stores still on the ships, de Luna sent several exploring parties inland to scout the area. They returned after three weeks having found only one Native American settlement. Before they could unload the vessels, a hurricane swept through and destroyed most of the ships and cargo. With the colony in serious danger, most of the men traveled up the Alabama River to the village of Nanipacana (Nanipacna or Ninicapua), which they found abandoned; they renamed the town Santa Cruz and moved in for several months. Back in Mexico, the Viceroy sent two relief ships in November, promising additional aid in the spring.

The relief got the colony through the winter, but the supplies expected in the spring had not arrived by September. De Luna ordered the remainder of his force to march to the large native town of Coca, but the men mutinied. Bloodshed was averted by the settlement's missionaries, but soon after Ángel de Villafañe arrived in Pensacola Bay and offered to take all who wished to leave on an expedition to Cuba and Santa Elena. De Luna relented and agreed to leave, eventually returning to Mexico. The Pensacola settlement disbanded completely within several months of his departure. De Luna was appointed governor of Yucatan in 1563 and remained in that capacity until his death in 1571. The area would remain unsettled by European powers for the next 140 years.

In the late 17th century (1698) the French were seeking to settle near the mouth of the Mississippi River. To defend their holdings here, the Spanish constructed the Fort San Carlos de Austria and laid a foundation for what would become Pensacola. On May 14th, 1719, Governor of French Louisiana, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville arrived with his fleet and a large ground force of Indian warriors, attacked the fort, and took Pensacola for France. The Spanish commander of Pensacola, Metamoras, had not heard that war had been declared between France and Spain, and his garrison was so small that he felt it would be useless to resist so at four o'clock in the afternoon, he surrendered on the conditions that private citizens and property should not be disturbed and the garrison should march out with honors of war and be shipped to Havana in French vessels. Bienville left about sixty men at Pensacola and sailed away. The French, who had established settlements also further west at Mobile and Biloxi, held Pensacola and remained in control for three years. A hurricane drove the French from Pensacola in 1722 and they burned the settlement upon their retreat. The Spanish moved the town from the storm-vulnerable barrier island to the mainland. After years of contention the Perdido River (the modern border between Florida and Alabama) was agreed upon as the boundary between French Louisiana and Spanish Florida.

Florida attracted numerous Africans and African Americans from the southern British colonies in North America who sought freedom from slavery. Once in Florida, the Spanish Crown converted them to Roman Catholicism and gave them freedom. Those freed men settled in a community north of St. Augustine, called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first free black settlement of its kind in what became the United States. Many of those slaves were also welcomed by Creek and Seminole Native Americans, who had established settlements in the region at the invitation of the Spanish government.

In the treaty negotiations concluding the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War), France ceded to Britain the part of Louisiana east of the Mississippi River, notably excluding the Île d'Orléans, which includes New Orleans. A separate treaty transferred the rest of Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain in exchange for Cuba, which the British had captured during the war. As a result of these exchanges the British controlled nearly all of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi. Most of the Spanish population left Florida, and its colonial government records were relocated to Havana, Cuba. In 1767, the British moved the northern boundary of West Florida to a line extending from the mouth of the Yazoo River east to the Chattahoochee River (32° 28′north latitude), consisting of approximately the lower third of the present states of Mississippi and Alabama.

The newly acquired territory was too large to govern from one administrative center, and the British divided it into two new colonies separated by the Apalachicola River. British West Florida's government was based in Pensacola, and the colony included the part of formerly Spanish Florida west of the Apalachicola, plus the parts of French Louisiana taken by the British. The British colony of West Florida, with its capital at Pensacola, included all of the Panhandle west of the Apalachicola River, as well as southwestern Alabama, southern Mississippi, and the Florida parishes of modern Louisiana. West Florida included the important cities of Pensacola, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and, disputably, Natchez. In 1763, the British laid out Pensacola's modern street plan. This period included the major introduction of the slave-based cotton plantation economy and new settlement by Protestant Anglo-British-Americans and black slaves. British East Florida, with its capital at Saint Augustine, included the rest of modern Florida, including the eastern part of the Panhandle. It thus comprised all territory between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, with a northern boundary that shifted several times over the subsequent years. Both West and East Florida remained loyal to the British crown during the American Revolution, and served as havens for Tories fleeing from the Thirteen Colonies.Britain tried to develop the Floridas through the importation of immigrants for labor, but this project ultimately failed. Spain invaded West Florida and captured Pensacola in 1781. Spain received both Floridas after Britain's defeat by the American colonies and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, continuing the division into East and West Florida. They offered land grants to anyone who settled in the colonies, and many Americans moved to them. However, the lack of defined boundaries led to a series of border disputes between Spanish West Florida and the fledgling United States known as the West Florida Controversy.

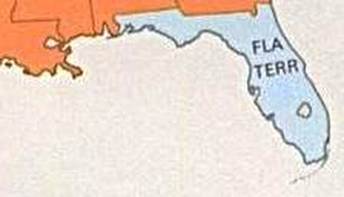

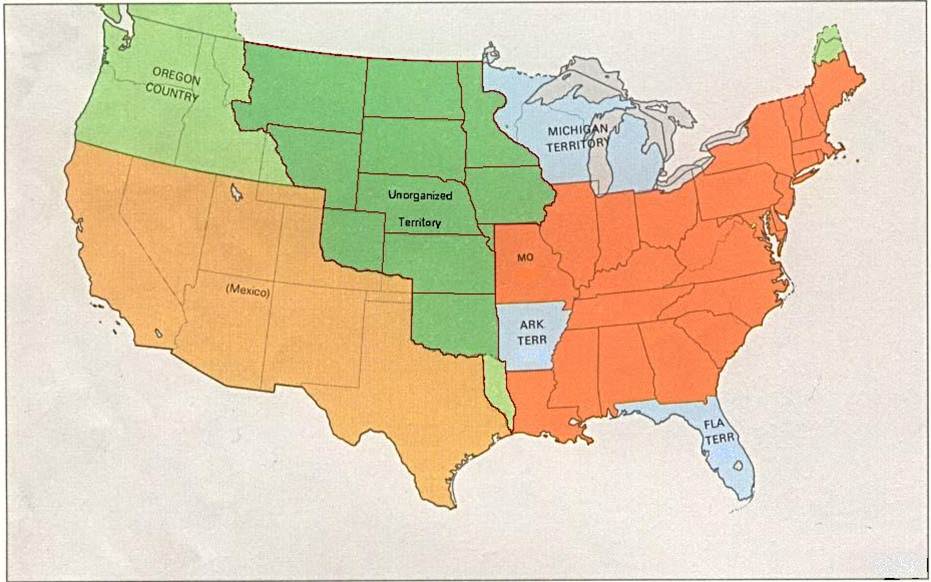

Florida Becomes a U. S. Territory

The British colony of West Florida, with its capital at Pensacola, included all of the Panhandle west of the Apalachicola River, as well as southwestern Alabama, southern Mississippi, and the Florida parishes of modern Louisiana. West Florida included the important cities of Pensacola, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and, disputably, Natchez. In 1763, the British laid out Pensacola's modern street plan. This period included the major introduction of the slave-based cotton plantation economy and new settlement by Protestant Anglo-British-Americans and black slaves. British East Florida, with its capital at Saint Augustine, included the rest of modern Florida, including the eastern part of the Panhandle.

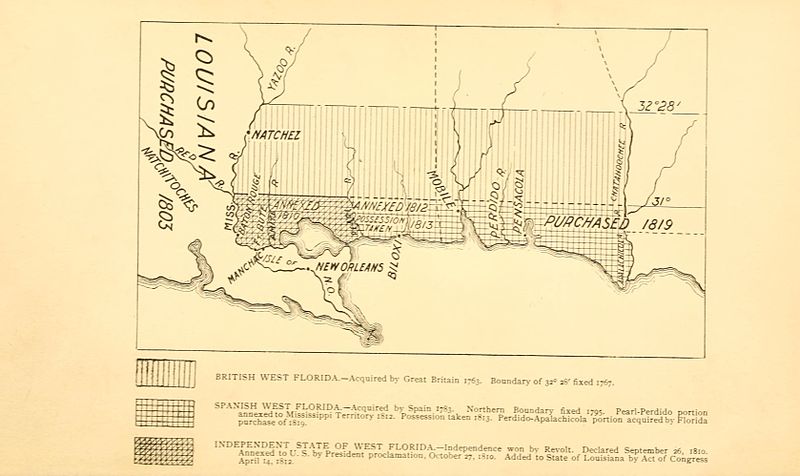

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), Georgia, including inland Alabama, revolted against the British crown, but East and West Florida, like the Canadian colonies, remained loyal to the British. Many British Loyalists, or Tories, settled in Florida during this period. Like the French, the Spanish allied themselves with the American rebels. In 1781, in the Battle of Pensacola, the Spanish attacked the British there and succeeded in capturing West Florida for Spain. At the end of the war with the American victory over the British, East Florida was also transferred to Spain.Disagreements with the Spanish government led American and English settlers between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers to declare that area the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810. This was soon annexed by the United States, which claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1810, the Republic of Florida is proclaimed by the people living there. At this point Florida is a new nation politically, but the reality is that the land is stilled owned by King Charles IV of Spain and this is a rebellion that must be defeated. Since the 19th century, many immigrants arrived from Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia.

After settler attacks on Indian towns, Seminole Indians based in East Florida began raiding Georgia settlements, purportedly at the behest of the Spanish. The United States Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. Following the war, the United States effectively controlled East Florida.

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), Georgia, including inland Alabama, revolted against the British crown, but East and West Florida, like the Canadian colonies, remained loyal to the British. Many British Loyalists, or Tories, settled in Florida during this period. Like the French, the Spanish allied themselves with the American rebels. In 1781, in the Battle of Pensacola, the Spanish attacked the British there and succeeded in capturing West Florida for Spain. At the end of the war with the American victory over the British, East Florida was also transferred to Spain.Disagreements with the Spanish government led American and English settlers between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers to declare that area the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810. This was soon annexed by the United States, which claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1810, the Republic of Florida is proclaimed by the people living there. At this point Florida is a new nation politically, but the reality is that the land is stilled owned by King Charles IV of Spain and this is a rebellion that must be defeated. Since the 19th century, many immigrants arrived from Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia.

After settler attacks on Indian towns, Seminole Indians based in East Florida began raiding Georgia settlements, purportedly at the behest of the Spanish. The United States Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. Following the war, the United States effectively controlled East Florida.

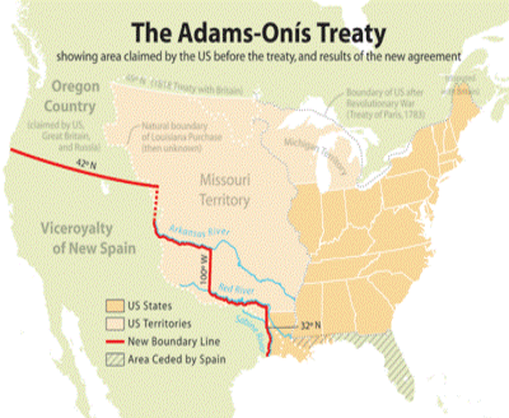

In 1819, the United States negotiated the purchase of the remainder of West Florida and all of East Florida by terms of the Adams-Onís Treaty. Spain ceded Florida to the United States in exchange for $5 million and the American renunciation of any claims on Texas that they might have from the Louisiana Purchase. East and West Florida were merged into the Florida Territory of the United States in 1822.

The free blacks and Indian slaves, Black Seminoles, living near St. Augustine, fled to Havana, Cuba to avoid coming under US control. Some Seminole also abandoned their settlements and moved further south. Hundreds of Black Seminoles and fugitive slaves escaped in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida to the Bahamas, where they settled on Andros Island.

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed and as settlement increased, pressure grew on the United States government to remove the Indians from their lands in Florida. To the chagrin of Georgia landowners, the Seminoles harbored and integrated runaway blacks, known as the Black Seminoles, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers. In 1832, the United States government signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing with some of the Seminole chiefs, promising them lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida voluntarily. Many of the Seminoles left at this time, while those who remained prepared to defend their claims to the land. The U.S. Army arrived in 1835 to enforce the treaty under pressure from white settlers, and the Second Seminole War began at the end of the year with the Dade Massacre, when Seminoles ambushed and killed or mortally wounded all but one in a group of 110 Army troops, plus Major Dade and seven officers, marching from Fort Brooke (Tampa) to reinforce Fort King (Ocala).

Between 900 and 1,500 Seminole Indian warriors employed guerrilla tactics against United States Army troops for seven years until 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent between $20 million and $40 million on the war, at the time an astronomical sum. A total of approximately 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were removed to Indian Territory; the US finally gave up its fight against the few hundred Seminole in Florida, who were deep in the Everglades and impossible to defeat or dislodge.

The free blacks and Indian slaves, Black Seminoles, living near St. Augustine, fled to Havana, Cuba to avoid coming under US control. Some Seminole also abandoned their settlements and moved further south. Hundreds of Black Seminoles and fugitive slaves escaped in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida to the Bahamas, where they settled on Andros Island.

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed and as settlement increased, pressure grew on the United States government to remove the Indians from their lands in Florida. To the chagrin of Georgia landowners, the Seminoles harbored and integrated runaway blacks, known as the Black Seminoles, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers. In 1832, the United States government signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing with some of the Seminole chiefs, promising them lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida voluntarily. Many of the Seminoles left at this time, while those who remained prepared to defend their claims to the land. The U.S. Army arrived in 1835 to enforce the treaty under pressure from white settlers, and the Second Seminole War began at the end of the year with the Dade Massacre, when Seminoles ambushed and killed or mortally wounded all but one in a group of 110 Army troops, plus Major Dade and seven officers, marching from Fort Brooke (Tampa) to reinforce Fort King (Ocala).

Between 900 and 1,500 Seminole Indian warriors employed guerrilla tactics against United States Army troops for seven years until 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent between $20 million and $40 million on the war, at the time an astronomical sum. A total of approximately 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were removed to Indian Territory; the US finally gave up its fight against the few hundred Seminole in Florida, who were deep in the Everglades and impossible to defeat or dislodge.

Florida becomes a State

|

Left - the Great Seal of the State of Florida

The Great Seal of the State of Florida is used to represent the government of the state of Florida, and for various official purposes, such as to seal official documents and legislation. It is also commonly used on state government buildings, vehicles and other effects of the state government. It also appears on the state flag of Florida. The seal features a shoreline on which a Seminole woman is spreading hibiscus flowers. Two of Florida's state tree, the Sabal palm, are growing. In the background a steamboat sails before a sun breaking the horizon, with rays of sunlight extending into the sky. The seal is encircled with the words "Great Seal of the State of Florida", and "In God we Trust". |

On March 3rd, 1845, Florida became the 27th state of the United States of America, located in the southeastern region of the United States. The state is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south by the Straits of Florida. White settlers continued to encroach on lands used by the Seminoles, and the United States government resolved to make another effort to move the remaining Seminoles to the West. The Third Seminole War lasted from 1855 to 1858, and resulted in the removal of most of the remaining Seminoles. Even after three bloody wars, the U.S. Army failed to force all of the Seminole Indians in Florida to the West. Though most of the Seminoles were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi, hundreds, including Seminole leader Aripeka (Sam Jones), remained in the Everglades and refused to leave. Their descendants remain there to this day and two tribes in Florida are federally recognized.

White settlers began to establish cotton plantations in Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. In the development of the Deep South, nearly one million African Americans were forced to move to the region through slavery. By 1860 Florida had only 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved. There were fewer than 1000 free African Americans before the Civil War.

White settlers began to establish cotton plantations in Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. In the development of the Deep South, nearly one million African Americans were forced to move to the region through slavery. By 1860 Florida had only 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved. There were fewer than 1000 free African Americans before the Civil War.

Florida and the Civil War

The catalyst for the secession of Florida was the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States in November 1860. Fearful that Lincoln and the Republican Party would seek to abolish slavery and thereby destroy the traditional economic and social order of the South, Florida secessionists, led by Governor Madison Starke Perry, called for the state to arm itself in preparation for secession from the United States and the creation of an independent Southern confederacy. The legislature met in regular session on November 26 and voted to call for the election of delegates to a state convention that would convene in January 1861 to decide for or against secession. Every delegate elected to the Convention of the People of Florida that assembled at Tallahassee on January 3, 1861, supported secession. Their main concern was not whether to secede, but when. The more moderate delegates, known as “cooperationists,” wanted to delay secession until several southern states were ready to leave the Union together. Radical or “fire-eater” delegates demanded Florida’s immediate withdrawal from the United States. The radicals won the debate: the convention passed an ordinance of secession on January 10. The next day, the convention assembled at the state capitol to sign the Ordinance of Secession, which declared Florida’s decision to dissolve its association with the United States and become “a Sovereign and Independent Nation,” making Florida the third state to leave the Union behind South Carolina and Mississippi.

On January 4, 1861, the first day of the secession convention, radical members of the convention met in private to authorize Governor Perry to seize federal military sites within the state. Governor Perry ordered state troops to seize the federal arsenal at Chattahoochee and Fort Marion at St. Augustine. Florida troops easily occupied the two undefended installations but failed to secure the more strategic federal positions at Key West, Dry Tortugas, and Pensacola, where Union troops remained in possession of Forts Taylor, Jefferson, and Pickens respectively.

Fort Pickens became the focus of particular concern between North and South as secessionist troops from Alabama and Mississippi rushed to Pensacola to reinforce the small force of Florida militia opposing the Union garrison at the fort. Similar to the situation at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, the military confrontation at Fort Pickens threatened to unleash civil war. The fact that the first shots of the war did not come from Florida was due to the South’s lack of a national government to coordinate strategy among the seceding states (the Confederate government did not exist until February 1861) and the hope that negotiations might secure Fort Pickens for Florida without bloodshed. When war finally came at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the standoff at Fort Pickens continued, but receded in importance as the focus of the war shifted to the front in Virginia. Despite a Confederate assault on Santa Rosa Island—the site of Fort Pickens—on October 9, 1861, the fort remained in Union hands throughout the war. It is this period of changing political structures that earned Pensacola the nickname "The City of Five Flags."

Florida’s role in the American Civil War spanned the entire conflict. From the earliest days of secession , when war threatened to break out in Pensacola, to the final surrender of Confederate forces in Florida in May 1865, Floridians experienced all aspects of the war that the South faced as a whole: economic hardship, naval blockade, internal dissension, battle, and final defeat. The war ended in 1865. On June 25, 1868, Florida's congressional representation was restored.

After Reconstruction, white Democrats succeeded in regaining power in the state legislature in the 1870s. In 1885 they created a new constitution, followed by statutes through 1889 that effectively disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites over the next several years. Provisions included poll taxes, literacy tests, and residency requirements. Disfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained federal legislation in 1965 to enforce protection of their constitutional suffrage.

On January 4, 1861, the first day of the secession convention, radical members of the convention met in private to authorize Governor Perry to seize federal military sites within the state. Governor Perry ordered state troops to seize the federal arsenal at Chattahoochee and Fort Marion at St. Augustine. Florida troops easily occupied the two undefended installations but failed to secure the more strategic federal positions at Key West, Dry Tortugas, and Pensacola, where Union troops remained in possession of Forts Taylor, Jefferson, and Pickens respectively.

Fort Pickens became the focus of particular concern between North and South as secessionist troops from Alabama and Mississippi rushed to Pensacola to reinforce the small force of Florida militia opposing the Union garrison at the fort. Similar to the situation at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, the military confrontation at Fort Pickens threatened to unleash civil war. The fact that the first shots of the war did not come from Florida was due to the South’s lack of a national government to coordinate strategy among the seceding states (the Confederate government did not exist until February 1861) and the hope that negotiations might secure Fort Pickens for Florida without bloodshed. When war finally came at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the standoff at Fort Pickens continued, but receded in importance as the focus of the war shifted to the front in Virginia. Despite a Confederate assault on Santa Rosa Island—the site of Fort Pickens—on October 9, 1861, the fort remained in Union hands throughout the war. It is this period of changing political structures that earned Pensacola the nickname "The City of Five Flags."

Florida’s role in the American Civil War spanned the entire conflict. From the earliest days of secession , when war threatened to break out in Pensacola, to the final surrender of Confederate forces in Florida in May 1865, Floridians experienced all aspects of the war that the South faced as a whole: economic hardship, naval blockade, internal dissension, battle, and final defeat. The war ended in 1865. On June 25, 1868, Florida's congressional representation was restored.

After Reconstruction, white Democrats succeeded in regaining power in the state legislature in the 1870s. In 1885 they created a new constitution, followed by statutes through 1889 that effectively disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites over the next several years. Provisions included poll taxes, literacy tests, and residency requirements. Disfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained federal legislation in 1965 to enforce protection of their constitutional suffrage.

West Florida Defined

Above - Ongoing changes to West Florida are identified

|

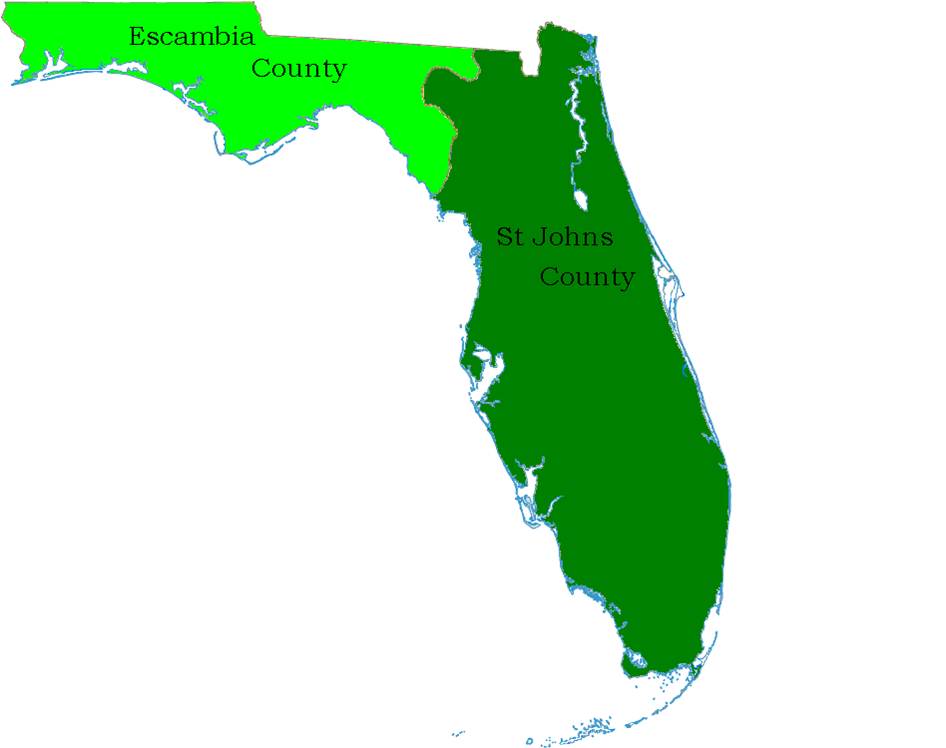

July 21st 1821 - Escambia County, (formerly West Florida) and St Johns County, (formerly East Florida) are created and a new line of division is decreed. The Suwannee River becomes the line of division, located east of the former Flint / Chatahoochee River border. The word Escambia has a disputed origin but may possibly originatate from the Native American word Shambia, meaning "clear water"

|

1822 - Florida becomes an Official Territory of the United States

|