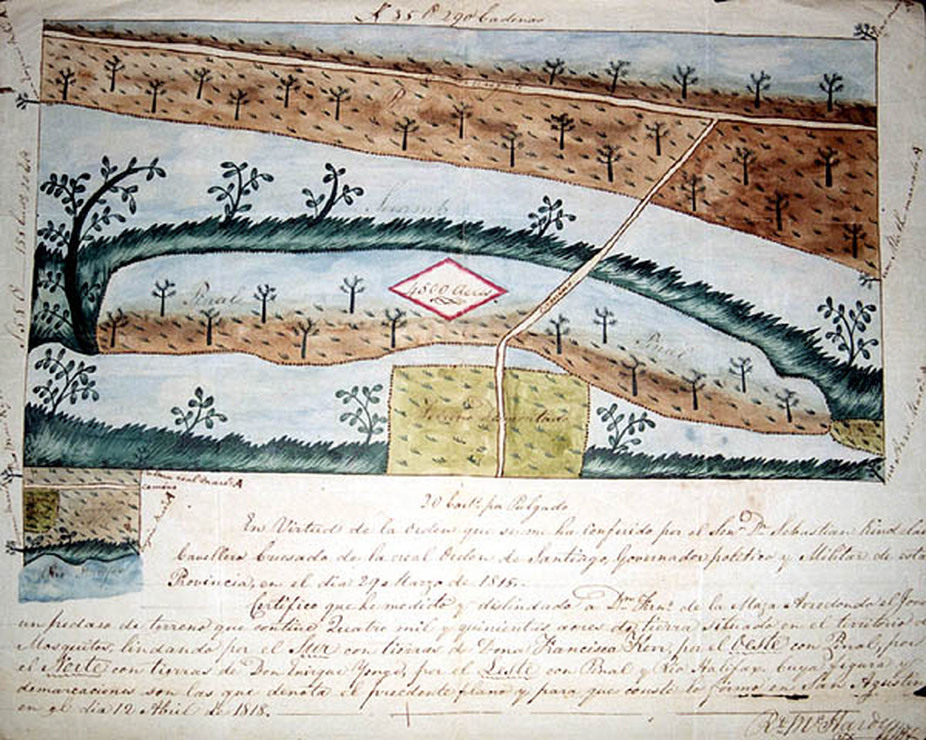

Spanish Land Grant Claim Survey Map, ca. 1818

Spanish Land Grant Claim Survey Map, ca. 1818 (From: U.S. Board of Land Commissioners, Confirmed Spanish Land Grant Claims, 1763-1821, Series S990)

Hand-colored plat maps such as this one by Surveyor Robert McHardy are among the documents used to establish ownership of land in Florida after it became a territory of the United States in 1821. The U.S. Board of Land Commissioners was established in 1822 (3 U.S. Statute 709, May 8) to settle all outstanding Spanish land grant claims in the territory that Spain ceded to the United States the previous year. The Board set up offices in Pensacola and Saint Augustine to determine the validity of all titles and private claims to these lands and either supported or rejected the claims based on its review of the documents submitted by claimants. This series is comprised of claims files containing those supporting documents, including petitions or memorials to a governor for land; surveys or plats; attestations; deeds of sale, gifts, wills, bequests, and exchanges; and translations of original Spanish land documents.

There are 932 confirmed land grants that can be researched at floridamemory.com Unfortunately, most of the records for West Florida are missing.

There are 932 confirmed land grants that can be researched at floridamemory.com Unfortunately, most of the records for West Florida are missing.

A Confirmed Grant in Walton County

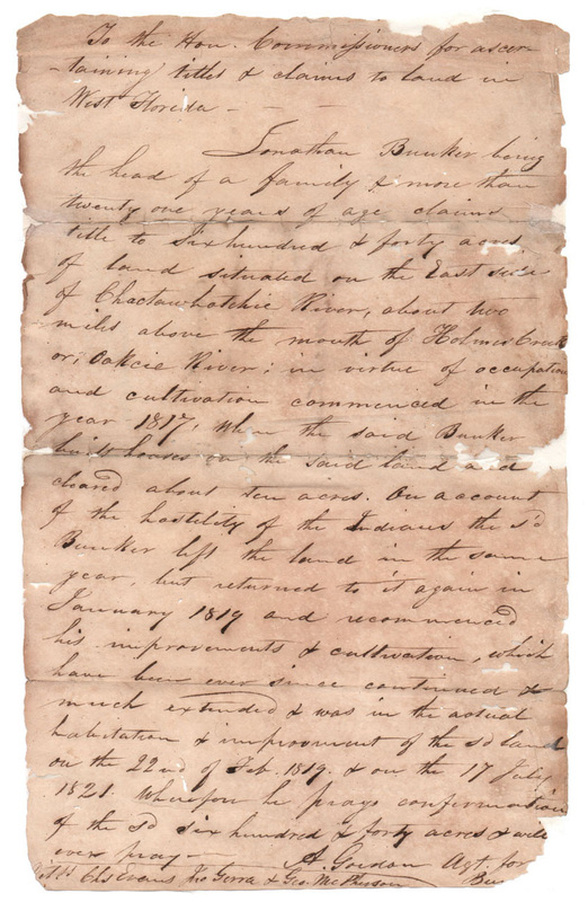

Land grant to Jonathan Bunker for 640 acres east of the Choctawhatchee River in a portion of Walton County, now Holmes County - confirmed in 1825

|

Left and Above

This confirmed land grant is a rare document for the central portion of the Florida panhandle area. Unfortunately, most of the land records for West Florida are missing from Local, State, and Federal records, including land grants and early deed conveyances. Walton County government offices lost important public records on 2 separate occasions. In 1830, there was a fire at the first Walton County court house in Alaqua and the public records are lost. Eucheeanna became the 2nd location for the county seat of Walton County until the courthouse was burned by an arsonist or by accident in May 1885. Once again, all public records are lost. Local folklore claims both fires were created by people involved with land disputes. On May 27, 1886, a commission approved moving the Walton County seat to DeFuniak Springs. The new courthouse is made from stone and brick. |

Spanish Land Grants

What were the Spanish Land Grants? The Spanish Land Grants were land claims filed by settlers in Florida after the transfer of the territory from Spain to the United States in 1821 in order to prove land ownership. Starting in 1790, Spain offered land grants to encourage settlement to the sparsely populated and vulnerable Florida colony. When the United States assumed control of Florida, it agreed to honor any valid land grants. Yet residents had to prove that validity through documentation and testimonials. Therefore, these records were the dossiers filed by grantees to the U.S. government. They were either confirmed (found to be valid) or unconfirmed (found invalid) by the US government through land commissions, federal courts, or by the U.S. Congress.

Unfortunately, most of the records for West Florida are missing.

What do the records tell us? The grants provide information on the settlement and cultivation of Florida during the Second Spanish Period (1783-1821) and the Territorial Period (1821-1845). Grantees had to provide the following information: description of land granted; date of grant; size of grant; property boundaries; and proof of residency and cultivation. Therefore the records contain surveys and plats, copies of royal grants, testimonials; correspondence, deeds, wills, and translations of Spanish documents. A note of caution: because many of the grants conflict and overlap with each other, not all of the information in the records can be considered accurate. Some of the surveys were not verified on the ground, nor was there a complete survey for Florida until the late 1820s. Serious researchers should also consult other land collections (see Related Resources).

An interesting paper written on the subject:

The Impact of Spanish Land Grants on the Development of Florida and the South Eastern United States by Dr. Joe KNETSCH, USA

ABSTRACT - The paper discusses the development of Florida and the Southeastern United States in light of the numerous and confusing system of Spanish Land Grants. The author argues that the development of Florida, and parts of the Southeastern United States, may have developed at a more rapid pace if the confusion caused by conflicting land claims had not interfered. It is shown that land grants given to British officers and favorites caused concern with land title validity on the early frontier. Spanish co-option of these claims further increased the confusion of title and acted as an inhibitor to settlement. Greater problems arose from the fraudulent claims and liberal interpretation given the powers of the Surveyors General, especially in East Florida. The acceptance of fraudulent evidence in West Florida and the

Florida Parishes of Louisiana indicated some corruption of early American officials that also retarded settlement. The final, and most important, cause of slower settlement of these areas was the problem of grant location by the United States Deputy Surveyors. Until these grants were properly located and laid out, few Federal surveys could be conducted. Without proper survey lines and the tying in of the land grants to the rectangular system, no safe title could

be given out. This lack of certain title to land acted as a blockage to a more rapid development and settlement on the Southeastern frontier of the United States, especially in Florida. View Document in it's entirety at www.fig.net

Another interesting paper on the subject:

Negotiating the Maze: Tracing Historical Title Claims in Spanish Land Grants . . .

by Sidney F. Ansbacher and Dr.Joe Knetsch

V. BACKGROUND OF SPANISH LAND GRANTS

Spain ruled Florida through civil law. The Florida Supreme Court discussed the Spanish colonial law as to waterfront lands at length in Apalachicola Land & Development Co. v. McRae: When Spain acquired territory by discovery or conquest in North America, the possessions were vested in the crown; and grants or concessions of portions thereof were made according to the will of the monarch. While the civil law was the recognized jurisprudence of Spain and its rules were generally observed, yet the crown could exercise its own discretion with reference to its possessions.

Under the civil law in force in Spain and in its provinces, when not superseded or modified by ordinances affecting the provinces or by edict of the crown the public navigable waters and submerged and tide lands in the provinces were held in dominion by the crown . . . and sales and grants of such lands to individuals were contrary to the general laws and customs of the realm.

"By the laws and usages of Spain the rights of a subject or of other private ownership in lands bounded on navigable waters derived from the crown extended

only to high-water mark, unless otherwise specified by an express grant."

This decision was recently re-examined and reconfirmed in the First District Court of Appeal in Florida in Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund v. Webb.

As the McRae court noted, Great Britain divided Florida into East and West Florida during British occupancy from 1763 to 1783.82 The Chatahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers split East from West Florida. Spain retained the East/West split when Florida reverted from Great Britain to Spain in 1783. Florida became subject to United States law under the cession from Spain to the United States, effective in July, 1821. The Treaty of Amity, Settlement and Limits Between

the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty, the King of Spain (“Adams-Onis Treaty”) established the terms of cession from Spain to the United States.

The pertinent portion of the authoritative Works Projects Administration (“WPA”) work, Spanish Land Grants in Florida (November 1940) (“Spanish Land Grants”), states the following regarding the effect of the Adams-Onis Treaty:

"By Article VIII of the treaty of February 22, 1819, whereby Spain ceded the Floridas to the United States, all Spanish grants of land made prior to January 24,

1818, the date on which the King of Spain definitely expressed his willingness to negotiate, were to be ratified and confirmed to the persons in possession of the lands, to the same extent that the said grants would be valid if the territories had remained under the domain of his Catholic Majesty."

The WPA book explicates the methods for confirming title. For example, a petitioner who sought confirmation of a Grant in what is today St. Johns County first obtained confirmation from the federal Board of Commissioners for East Florida if the Grant was under 3,500 acres in size, and, in turn and as appropriate, from Congress. The principal federal records of United States confirmations of such Grants are in the “American State Papers,” particularly, the pertinent American State Papers containing records of Congress relating to disposition of confirmation applications. Other important records include copies of the original documents of confirmation, which are available on microfiche, and the actual proceedings of the board of Commissioners for East (and West) Florida. The original

documents often include copies of the original surveys.

The United States agreed to confirm title to valid Spanish Land Grants under the Adams-Onis Treaty. The transfer of Florida was specifically made subject to any pre-existing Spanish land grants:

"[A]ll the grants of land made before the 24th of January, 1818, by his Catholic majesty, or by his lawful authorities, in the said territories ceded by his

majesty to the United States, shall be ratified and confirmed to the persons in possession of the lands, to the same extent that the same grants would be valid if

the territories had remained under the dominion of his Catholic majesty."

The Adams-Onis Treaty also granted an extension of time for grantees who had not yet fulfilled the terms of their grants to do so:

"But the owners in possession of such lands, who, by reason of the recent circumstances of the Spanish nation, and the revolutions in Europe, have been prevented from fulfilling all the conditions of their grants, shall complete them within the terms limited in the same, respectively, from the date of this treaty...."

Subsequent to the Adams-Onis Treaty, various acts of Congress were passed for settling private land claims in the ceded territories, pursuant to Article 8 of the Treaty, which provided that grants of land made before the 24th of January, 1818, . . . in the said territories . . . shall be ratified and confirmed to the persons in

possession of the lands, to the same extent that the same grants would be valid if the territories had remained under the dominion of” Spain. While Spain ceded over East Florida and West Florida, Congress implemented Article 8 of the Treaty by ratifying and confirming Spanish Land Grants made prior to January 24, 1818,

according to its terms.

The United States Supreme Court in United States v. Arredondo addressed at length the great legal weight afforded to Spanish Grants in Florida under the Adams-Onis Treaty and amendments to that Treaty:

"Yet, in [Congress’] whole legislation on the subject (which has all been examined), there has not been found a solitary law which directs; [sic] that the authority on which a grant has been made under the Spanish government should be filed by a claimant-- recorded by a public officer, or submitted to any tribunal appointed to adjudicate its validity and the title it imparted--[C]ongress has been content that the rights of the United States, should be surrendered and confirmed by patent to the claimant, under a grant purporting to have emanated under all the official forms and sanctions of the local government. This is deemed evidence of their having been issued by lawful, proper, and legitimate authority--when unimpeached by proof to the contrary."

The Arredondo court explained that the acts of the Spanish Colonial government and surveyor in issuing the grants and supporting surveys were “deemed” presumptively authorized “by the order and consent of the [Spanish] government.”96 But this was not always the case, and the U.S. Supreme Court at times had refused confirmation on numerous legal grounds, most often for lack of proper survey or vague boundary descriptions.

The Florida Supreme Court has held that Lands Act parcels could not contain lands that Spain had granted prior to cession:

"Under that treaty, the United States acquired the ownership of all the swamp and overflowed lands in the area now constituting the territorial limits of the state of Florida that had not previously been granted by Spain . . . ."

View Document in it's entirety at www.fig.net

Spain's Land Policy:

The land policy of Spain's first regime in Florida was based on the Law of the Indies, which was a codification in 1680 of the royal cedulas — the orders, provisions, ordinances and instructions under which Spain's colonies had previously been governed, At the same time the Council of the Indies was established at the Spanish court with absolute authority under the King in dealing with colonial matters .Land was granted to individuals in peonias and caballerias, according to rank, a distinction being made between laborers and gentlemen. Originally the peonia was a grant made to peon (foot soldier); the caballeria, a grant to an esudero (squire) who was generally a mounted trooper. With the exception of the lot on which the residence was built, a caballeria was five times that of a peonia. The term caballeria came to mean, in Mexico, a piece of land granted for the purpose of raising horses or cattle, and measured 1,104 varas long by 552 varas wide, or 609,408 square varas.

In Florida, a peonia was a lot of fifty feet in breadth and one hundred in depth; sufficient arable land to produce 100 fanegas of wheat and barley and 10 of Indian corn; two huebras for a garden and eight huebras of woodland; pasture land for ten breeding sows, twenty cows, five breeding mares, one hundred ewes and twenty goats. A caballeria consisted of a lot of one hundred by two hundred feet and five times as much arable land, pasture, etc. as in a peonia. Houses were to be built and lands cultivated within a given time under penalties provided by law. If possession was not taken within three months the land was forfeited to the crown.

No stranger (alien) was permitted to trade with the Indies except those who had been licensed by the King, and they were under surveillance and forbidden to reside in port towns. Naturalization required residence in the Kingdom or in the Indies twenty consecutive years, the ownership of a house and real property to the value of 4,000 ducats, and marriage with a native, or daughter of a stranger, born in the Kingdom or in the Indies. Even with these conditions satisfied the naturalized citizen could not trade or contract without the sanction of the Council of the Indies, and if licensed he could trade only with his own funds and after filing with the court under oath an inventory of his possessions.

Although the Law of the Indies was useful to United States Boards of Commissioners in interpreting claims, no grant was presented to them under its provisions. The earliest grant brought before them was of English origin, dated 1765.

After the retrocession of the Floridas, Spain adopted in part the policy the English had followed in granting lands. Under the royal order of 1786 British subjects in Florida were permitted to remain and retain possession of their lands by taking the oath of allegiance to Spain. Efforts to attract Irish Catholics as settlers having in large part failed, the King issued the royal order of 1790 inviting aliens to Florida regardless of their religious affiliation. Grants under this order were popularly known as "head rights". Under the regulations issued by Governor Quesada, immigrants who would take the oath of allegiance and could furnish transportation for themselves, their families and goods, and who could be self-supporting until they were established, were invited to come in and receive free land. They were promised freedom in matters of religion, although only the Catholic worship was to be permitted in public. The head of a family was offered 100 acres of land with 50 acres for each white or colored person in the family, whatever their ages. An additional grant up to 1,000 acres could be obtained if there was probability of its being cultivated. The grantee could not during his probation alienate the land without the consent of the government, but must hold and cultivate it continuously for a term of 10 years. He was required to build a house with a suitable chimney, prescribed by the regulations, to build fences and to keep a certain number of livestock. When his tenure and improvements were proved by the testimony of witnesses under oath, a title in absolute property would be issued. (47)Captain Pedro Marrot of the 3rd Battalion of Infantry, garrisoned at St. Augustine, was chosen to supervise the surveys and was given minute instructions. He was to take with him the public surveyor and to see that measurements were made according to the general regulation and the terms of any particular grant. He was to ascertain that applicants had taken oath of allegiance, make a list of the white and black members of each family, noting their sex and ages, and take the oath of the applicant on those points. Surveys were to be so made that the length would extend inland and be two-thirds more than the width, or frontage. Owners of adjacent lands were to be cited to appear and exhibit their titles and the lines were to be run accordingly, the matter to be later reviewed by the government. Even the physical equipment and the size of the surveying party were specified: in addition to the public surveyor, Marrot was to take four sailors and two laborers, a canoe two tents and two tarpaulins. He was to record "in a large book" all the pertinent facts of each survey.

Although the royal order of 1790 had been issued with the expectation of attracting aliens, Spanish subjects claimed head rights under its terms and accepted the longer tenure because of the more generous allotment it offered over those prescribed in the Law of the Indies.

In the following thirteen years the intent of the law was often disregarded by new settlers and to prevent the abuses which had come to be customary, Governor White in 1803 issued new regulations. Only 50 acres were to be allotted to heads of families and none for children under eight years of age. For children and slaves between eight and sixteen years, 15 acres were allowed; 25 acres for those who were sixteen and over. To those who sold or conveyed their lands before they had acquired title, other grants were denied and the conveyances were illegal unless sanctioned by the government. When no other date was specified, grantees were required to take possession within six months. If grants were made to those residing in towns, cultivation must begin within one month. To prevent fraud and avoid

disputes, each petitioner was required to designate a point from which measurement was to begin, and he was to give up his improvements for the benefit of the royal treasury in the event a change of location should later be desired. Those who abandoned their lands or discontinued cultivation for a period of two years were to lose their rights and the lands might be receded by the governor to the persons making such proof.

In the absence of the public surveyor, Juan Purcell, in 1811, Jorge (George) J. F. Clarke was appointed to the office. (51) Clarke's instructions, like those of Marrot, were specific:

Article 1. He was to consider possessors of land under three classes—proprietors, those holding lands by title not obtained from the government; grantees, those who after compliance with conditions will receive titles; grantees and proprietors, those who have already fulfilled conditions and acquired titles.

Article 2. He was to demand title or grant before acceding to any request to measure or bound lands.

Article 3. He must cite owners of adjacent lands to appear with their titles and satisfy himself that there was no conflict between claims.

Article 4. He was to lay out grants in rectangular parallelograms, the narrower portion, fronting rivers, creeks, and roads, to be one-third the depth which was to extend inland. If necessary to prevent empty spaces, however, he was to increase the frontage and correspondingly decrease the depth.

Article 5. He was to give each grantee a plat, signed and dated, made on a certain scale, with perimeters, distances in chains and links, corners, magnetic directions and the number of acres, marked in ink.

Article 6. He was to retain a copy of each plat in a book the index of which would show the page of each plat, its number, and the name of the grantee. At the back of the book the surveys, each bearing the proper number, were to be drawn to a given scale.

Article 7. The book described in the foregoing article was designed to serve the purpose of showing the government what lands were unmeasured and exhibit the surveyor's operations so as to satisfy grantees as to their boundaries.

Articles 8, 9, and 10 gave instructions for making corners for tracts and a list of the fees the surveyor might charge.

In view of these explicit regulations and the tradition for meticulous care which Marrot had given to the office of surveyor-general and which had been continued by John Tate and Juan Purcell, Clarke's testimony before the United States Board of Commissioners denying that he had been bound by rules is surprising.

Despite generous land grants colonization lagged. Juan Estrada, appointed governor upon the death of Governor White in 1811, felt that the difficulty lay in requiring a ten-year tenure before title was granted, He accordingly proposed that the West Florida plan be adopted of selling the land and giving title in fee simple, which he thought would attract settlers from the United States. The captain-general of Cuba called his attention to the fact that by royal orders of 1804 and 1806 the admission of citizens of the United States was prohibited. (54).

The royal order of 1815 permitting grants for patriotic services was supposed to have been made in response to Governor Kindelan's recommendation two years earlier. The "Patriotic War" had just ended and the Governor suggested to Juan Ruiz de Apadacha, Captain-General of Cuba, that rewards be given to the three white militia companies and to the 3rd Battalion of Cuba: 1. to each of the militia officers, a royal commission for each grade possible to him as a provincial; and 2. to all soldiers of the militia and to the married officers and soldiers of the 3rd Battalion of Cuba, lands in proportion to the size of their families. He admitted that his plan would not in reality given them anything which was not already open to them, but he thought that "public approbation would content the men and stimulate their patriotism."

The authenticity of the copies of Kindelan's letters and of the royal order of 1815 was called into question by Alexander Hamilton, member of the United States Board of Commissioners for East Florida in 1823. He sent to Secretary of the Treasury Crawford "a translation of what is commonly called the Royal Order of 1815, together with a copy and translation of a letter supposed to have been written by Governor Kindelan, the apparent inducement to the order," under which he said "the numerous and extensive grants have been made." He asserted that there had been an erasure in Kindelan's letters and the word "extensively" substituted for "exclusively," making a sentence read "…which gifts can also be extensively made to the married officers and soldiers of the said third battalion of Cuba."

No other authority being available, the Board adjudicated service grants on the basis of the order and letter in question. No conditions were attached to such grants, but in the main their size was based upon head rights. The recital of services rendered often makes the memorials humorous reading.

Spanish land grants may thus be said to have been based upon three royal orders: that of 1786 for the English in Florida; that of 1790 for strangers, of which Spanish subjects also availed themselves; and that of 1815 for patriotic service. In addition there were two other types of grants which may be said to have contemplated future services to the province: saw or grist mill grants and cow pen (cattle ranch) grants. There was controversy between Alexander Hamilton and his colleagues as to the extent of discretion permitted to Spanish governors in the matter of land grants, and certainly no royal orders covered these types, but the Council of the Indies evidently did not disapprove of the action of the governor in making such grants.

Memorials for sawmill grants usually asked for five league square, or 16,000 acres, and urged the value to the province of mills such as they proposed to establish. They were readily granted, beginning in 1793. In every instance the governor made the establishment of the mill a condition precedent to the license to cut timber. In no instance save one was a perfect title to this type of grant conferred by Spanish authorities, since none fulfilled the conditions before the cession. The exception was the grant of 26,000 acres to George J. F. Clarke who claimed to have invented a sawmill to be propelled by animal power, and who in addition had served the government in various capacities, and especially in the Patriot War, when the rebels put a price upon his head and upon the heads of members of his family.

The United State Boards of Commissioners and later the Registers and Receivers of the land offices who took over the duties of the commissioners took the position that only a mill site and the right to cut timber over an area of 16,000 acres were granted. As Richard Keith Call, Receiver, put it, the grants were not intended to convey land but "a mere usufruct for the enjoyment of the timber." Call pointed out in his report to the Secretary of the treasury in 1835 that the land claimed under these twenty odd grants amounted to 312,600 acres, whereas the whole amount confirmed to grantees for habitation and cultivation—the paramount object of the laws and ordinances of Spain—from October, 1790, until the cession was only about 129,000 acres. (58) A few of the grantees fulfilled the conditions after the cession as permitted in the treaty, and the Supreme Court confirmed their claims.

The concession to Clarke was made December 17, 1817, and governor Coppinger at the same time gave complete title to 22,000 of the 26,000 acres granted. When Clarke had established the sawmill the Supreme Court confirmed his claim to 22,000 acres, but denied the validity of the title to 4,000 acres which had been completed after January 24, 1818, the date specified in the treaty as the last on which grants made by Spain would be recognized. Call was critical of the court's action in confirming the concession and plainly intimated that Governor Coppinger's object in making the grant was to defraud the United States.

Cow pen (cattle ranch) grants gave less trouble than did mill grants. In most instances conditions were fulfilled including tenure of ten years, after which titles were granted. Pablo Sabate's grant (61) of 2,500 acres for such a purpose was an exception. He received a royal title, without seemingly being called upon to meet any conditions whatever. This extraordinary title having been granted on April 2, 1818, the Board of Commissioners disallowed the claim as being contrary to the treaty.

In West Florida the terms for granting lands were somewhat different from those which obtained in East Florida. Governors there had changed frequently and lands were granted not only by the governors, but also by acting governors and intendants. In the main, the United States Board of Commissioners for West Florida followed the general regulations made on July 17, 1799, by Juan Venture Morales, who, to give his full title, was principal comptroller of the army and finances of the provinces of Louisiana and West Florida, intendant par interim and subdelegate of the superintendence, general of the same, judge of admiralty and of lands, etc., of the King, etc. These regulations provided for three types of grants: gratuities, lands sold, and compromise grants.

Gratuities, or conditional grants to colonists (a chaque famille nouvelle), were based upon the size of the family and were not in any case to exceed 800 arpens. These settlers were under the necessity of clearing and putting into cultivation a certain amount of land within the three-year tenure required. If the grant bordered the Mississippi River, the owner was in addition required during the first year to build levees, canals, a highway and bridges. Failure to comply with the conditions would prevent the sales of the land, which would revert to the crown.

The policy of selling land outright was preferred by the authorities of West Florida. The tax price (quitrent) was set by the King's agent and the lands were sold at auction. When purchasers did not have ready money with which to pay for their lands, they were permitted to buy them at redeemable quitrent during the continuance of which they paid 5% yearly. However, they were expected to pay down the right of media annala, or "half year's rent," to be remitted to Spain, and they had to pay the fees of the surveyor and notary.

Comprise grants were made to "squatters" who had cultivated and improved the land for ten years and who after investigation and assessment by the treasury paid "a just and moderate retribution, calculated according to the lands, their situation, and other circumstances," and the cost of making the estimate.

Whether lands were sold or donated, the King reserved the right of taking from them any timber he might need, particularly cypress for the navy.

There were usually seven steps in acquiring land under Spanish authority:

1. A memorial or petition to the governor setting forth the claimant's right to a service grant or to head rights, or a proposal to render a service to the province by erecting a mill or establishing a cow pen, and usually specifying the tract desired.

2. A review of the petition by the governor's office; if favorable, it was referred to the commandant of engineers to ascertain whether there were any objections from the standpoint of defense. The commandant frequently stipulated that the grantee should have no claim for damages if ordered to retire to the interior or if his buildings should be burned in case of military necessity. Particularly was this so if the grant lay within the mil y quinientas — the land within a radius of 1,500 varas from the flagstaff, outside the walls of fortified towns such as St. Augustine and Fernandina, which the King had placed at the disposal of the commandant for purposes of defense. The grant in the mil y quinientas was usually one acre, on which the commandant allowed the cultivation of low-growing crops, usually vegetables which the grower peddled in the town, and the building of a palm shack ten or eleven feet square and ten feet high. He forbade the digging of ditches and the building of picket fences, only rail fences being allowed.

3. A grant made by the governor, usually noted on the margin of the petition, giving the authority under which the concession was made and stating the conditions of settlements, cultivation, the bringing in of a certain number of slaves, etc., together with instructions to the surveyor-general. The grant, however, did not mean, as in the United States, a perfect title, but an incipient right which required confirmation by the governor at a later date. The petition was filed in the office of the escribano.

4. Verification of the petitioner's statements by the governor's office or the surveyor-general through the examination of witnesses. If the grant was for head rights, the number in the family, white and black, was ascertained, regarding which the petitioner made oath. The surveyor-general also ascertained whether there was a prior claim to the land in question. Having satisfied himself on these points he made the survey, entered it on his records and issued a certificate. The petitioner was now at liberty to take possession and begin fulfillment of conditions.

5. A memorial by grantee for absolute title.

6. Decree of the governor for taking testimony to prove whether conditions had been fulfilled.

7. Decree of the governor for absolute title, after which the owner could dispose of the land in any way he saw fit. Frequently a grantee became dissatisfied with his land and petitioned the governor for an exchange. If the reasons were good it was usually granted.

Titles issued by the Spanish government were therefore of two kinds: those in "absolute property" and "conditional." Conditional titles were represented by certificates of survey reciting the conditions to be fulfilled. Titles in absolute property were given when all conditions had been fulfilled or when grants were made for services already performed. Under the law of the Indies the term required for a perfect, or complete, title was four years of inhabitation and cultivation; under the royal order of 1790 and Governor Quesada's regulations, ten years; under Governor Kindelan, whenever improvements had been made, regardless of the number of years. Kindelan's regulation, issued in 1815, was made necessary by the conditions following the Indian wars and revolutions, which drove many people from their lands and prevented the fulfillment of conditions within the time specified in the grants. Once a title in absolute property was obtained, the possessor of land, his heirs, and assigns, had the power to discontinue cultivation, to sell, cede, exchange, transfer and alienate at will.

By Article VIII of the treaty of February 22, 1819, whereby Spain ceded the Floridas to the United States, all Spanish grants of land made prior to January 25, 1818, the date on which the King of Spain definitely expressed his willingness to negotiate, were to be "ratified and confirmed to the persons in possession of the lands, to the same extent that the said grants would be valid if the territories had remained under the domain of his Catholic Majesty." Owners in possession of such lands who, by reason of the recent circumstances of the Spanish nation and the revolutions, had been prevented from fulfilling all the conditions of their grants, were to be permitted an equal time to complete them after the date of the treaty. Grants subsequent to January 24, 1818, were to be considered null and void. The treaty was not ratified and proclaimed until February 22, 1821 and yet another year passed before a permanent territorial government was established in Florida by the Act of March 30, 1822.

On May 8, 1822, Congress passed what proved to be the first of a series of Acts designed to carry out the provisions of Article VIII of the treaty of cession. The Act provided for the appointment by the President of three commissioners who on or before the first Monday in July, 1822, should open an office at Pensacola for the adjudication of land claims in West Florida. They were to hold sessions also at St. Augustine, for the purpose of passing on similar claims in East Florida. The sessions were to terminate on June 30, 1823, when the commissioners should forward to the Secretary of the Treasury, to be submitted to Congress, a record of all they had done and deliver over to the surveyor all archives, documents, and papers in their possession.

The commissioners were authorized to appoint a suitable and well qualified secretary, acquainted with the Spanish language, who should record in a well-bound book their acts and proceedings, including claims admitted and rejected, with the reason for their admission or rejection.

Persons claiming title to lands under any patent, grant, concession, or order of survey, dated prior to January 24, 1818, which were valid under the Spanish government, or by the law of nations and which were not rejected by the treaty ceding the Floridas to the United States, were instructed to file their claims before the commissioners, with supporting evidence, and, where claimants were not the original grantees, with deraignment of title. Claims not filed before May 31, 1823, were to be null and void.

With reference to titles derived from British grants, the commissioners were to consider only such as were claimed by citizens of the United States and which were valid under the Spanish government and had never been compensated for by the British government.

To facilitate their inquiries the commissioners were authorized to administer oaths and to compel the attendance of witnesses, and were granted access to and the right to make transcripts of all public records relative to land titles. They were empowered to confirm all valid claims under 1,000 acres, but were directed to report to the Secretary of the Treasury, for the action of Congress, all testimony concerning claims in excess of that amount or of undefined quantity, with their opinion thereon, and the testimony concerning conflicting claims emanating from both the British and Spanish governments.

The first meeting of the commissioners was held in Pensacola on July 15, 1822, with Samuel R. Overton and Nathaniel A. Ware present. Business transacted was the appointment of Joseph M. White as secretary, to whom written instructions were given concerning his duties, and the adoption of rules to be observed by all claimants. Claimants were requested to file a written petition or notice setting forth the boundaries of the land claimed, evidence in support of their claims, and deraignment of title, together with a brief reference to the laws and ordinance under which the grants were made.

The secretary was instructed: 1. to keep in the minutes "a record of the meetings and adjournments of the commissioners, with a statement of their proceedings and decisions accompanied by the evidence on which the decisions were made"; 2. "to record in their original language, all the papers necessary to the establishment of the title, with the reason of their admission or rejection," in the following order: notice or petition, notarial certificate of sales and transfers, mesne conveyances so abbreviated as to show the claim of title and date of transfer, the patent, grant, or concession, report of the surveyor as to whether the land was vacant, report of fisc. stating whether there were any objections to the petition, order and certificate of survey and the plat (if the survey was executed prior to January 24, 1818); and 3. to file in his office, for the inspection of the commissioners when considering claims, all papers not recorded. The secretary was further instructed that translations would be confined to recorded papers and such other documents as the commissioners might from time to time require.

Having organized and adopted rules of procedure, the commissioners were ready to receive claims. Few were forthcoming. Only four meetings, including the first, were held in July. A fifth session was held on August 16. Four days later the minutes record: "In consequence of the appearance of a malignant fever in the City of Pensacola, and the impracticability of either remaining in safety or of doing business, ordered that the Court be adjourned until further appointment." It reconvened on October 4, only to adjourn until December 12.

Congress had not supplied the commissioners with published copies of Spain's land laws, nor indeed were copies easily obtained in this country. Throughout what came to be a three-year term the commissioners were handicapped in this particular. As late as November 12, 1824, they complained that they had been unable to obtain a copy of the ordinance of 1754 issued by Ferdinand VI and that very few settlers would answer questions concerning land laws and practices. Not until Joseph M. White complied from his experience as secretary and commissioner of the Board for West Florida and from published works, which he finally obtained from Spain, his "Spanish and France Ordinances Affecting Land Titles in Florida and Other territories of France and Spain" was there an adequate guide for the adjudication of Spanish land claims in Florida.

On December 12, 1822, the Board issue an order "to summon the most respectable Spanish Inhabitants to give evidence in relation to the customs and practice of the Spanish Officers of the provincial Government" with reference to land grants, and four days later these citizens appeared before the Board.

In all, nine sessions were held between July 15 and December 16, 1822 It was evident that the date limits set forth in the Act of May 8, 1822, had not given sufficient time for the business in hand, and the commissioners apparently made no effort to comply with its provisions for holding sessions in St. Augustine.

On March 3, 1823, Congress provided for two Boards of Commissioners, who were to hold sessions in East and West Florida, at St. Augustine and Pensacola respectively, until the second Monday in February, 1824. Claimants were no longer required to produce in evidence deraignment of titles, and the commissioners were authorized to confirm claims up to 3,500 acres instead of 1,000 as provided in the law of 1822. District attorneys when required to do so were to attend sessions of the Boards for the purpose of arguing and explaining points of law. Claims not filed before December 1, 1823, were to be considered null and void.

It required six weeks for the Act of March 3, 1823, to reach West Florida. A session of the Board was called for April 19, but only Samuel R. Overton was in the territory and present. No further meeting was held for four months. On September 2 the Board was reorganized, Joseph M. White being sworn in to replace James P. Preston, resigned. Morris Hunter of Pensacola was appointed secretary to succeed White.

The Board set itself the task of hearing claims for three town lots or two tracts of land each day and met regularly until February 9, 1824, when, the time limit set for its sessions having expired, it adjourned "until further order" with its business still unfinished. Its life was extended to January 1, 1825, by the Act of February 28, 1824, and the commission reconvened with the same personnel on April 5, 1824. On May 4 Craven P. Luckett succeeded Ware and Overton failed to sit at any session recorded after May 20, (94) although he signed the reports of the Board to the Secretary of the treasury on November 12, 1824, and January 12, 1825.

There is no record in the minutes of a session after July 19, 1824, but White and Luckett evidently continued to transact business during the remainder of the year and even subsequent to January 1, 1825, for an Act of Congress of April 22, 1826, legalized their activities after that date. Afterwards the Register and Receiver for the Land Office of West Florida.completed the work in which the commissioners for that district had for three years been engaged.

The three commissioners appointed for East Florid were Davis Floyd, William F. Blair, and Alexander Hamilton. At the first meeting of the Board on August 4, 1823, Floyd was elected chairman and Francisco Jose Fatio was appointed secretary. John Lowe was appointed messenger; Joseph Lancaster was sworn in as deputy to the secretary.

The board adopted unanimously the following regulations:

"All persons claiming title to lands under any patent, grants, concession, or order of survey, will make a brief statement, by Memorial, setting forth the situation, boundaries, and if possible, the deraignment of title, to the Lands claimed, and by whom granted, and by what authority, and whatever the same be the whole or part of the original grant."

"All cases where grants have been mad eon conditions it will be necessary to show the nature of the conditions, whether they have been performed and if not the reasons why they have not been complied with."

"Where lands are claimed by actual settlers, without grants, concessions, patents, on orders of survey, the same must be declared, occupancy stated distinctly, together with the nature of the evidence, in support of the claim; and whether the said possession ever was and in what manner acknowledged or sanctioned by the Spanish government."

"In all instances where claims are made in virtue of British Patents, grants, etc., the claimants must describe in what manner they claim, whether as original patentees or Grantees or by assignment, also whether they are in actual possession, and if out of possession that they claim 'bona fide' as American Citizens."

"All original documents if in possession of the claimants must be exhibited and in other cases certified copies, the Memorial, order of Survey, Survey and confirmation, together with the translations of the same."

"Claimants must show whether they were actual residents at the time of the cession and where they now reside."

Rules adopted by the Board for its guidance included, among others:

"Resolved that claimants be not required to produce their title papers translated into the English Language, but in all cases be permitted to file the original documents—the Honorable Alexander Hamilton dissenting."

"Resolved, that hereafter whenever a claimant of Land shall present his evidence of title to the Secretary of this Board desiring to bring the same before the commissioners, it shall be the duty of said Secretary without any fee therefore, to put the same in the form of a Memorial, containing in substance what has already been required by the resolution of this Board. And that the said Secretary be authorized too obtain from the Printer in this city One thousand blank copies of said form & authorize said printer to present his account therefore, before this board who will direct the said account to be paid out of any monies which may come into their hands for appropriations — or in case of none such will certify said account to the Treasurer of the United States."

"And be it further ordered that the Secretary be required to deliver one of these printed forms to any person or persons applying for the same."

On three occasions the following resolution was offered before it was adopted on November 28:

"Resolved that claimants desiring to obtain the testimony of any witness residing without the Territory of Florida shall file with the Secretary their Interrogatories; and that the District Attorney under the direction of the Board shall if required, annex Cross Interrogatories, on behalf of the United States—and that in all cases where the Witnesses are residents within the Territory, the claimant may file depositions taken 'Ex parte' as the said witnesses are subject to the jurisdiction of the Commissioners: leaving it optional with the Claimants to procure by filing interrogatories, and that a commission with the interrogatories so annexed shall be directed to any person authorized to administer oaths, sealed by the Secretary and delivered to the party so making application and it shall be the duty of said person to take the answers of said Witness to all such interrogatories and none other, and to certify the same, and whether the said Commission was sealed when delivered."

On December 9 it was ordered that "the Rules of evidence governing Courts of Law, govern the Board for the future—viz., that the party calling the Witness, first examine him, & then turn him over to the District Attorney, and when he has finished the Board can ask him any pertinent question which they conceive to have been omitted; but the party examining the witness, cannot be interrupted without he is putting an improper question—Mr. Hamilton dissented as to any restraint on the Board in its examination." The Board adjourned sine die on February 9, 1824.

The difficulties with which the commissioners had to contend were enumerated in their report at the end of the year. The law required that all Spanish documents be translated and recorded, but allowed only one secretary. No means of collecting fees for translating papers for claimants having been provided by Congress and the fees being too small to justify collection by the orderly processes of law, no funds from that source were available for employing additional clerks. To meet the situation the commissioners required the secretary to hire an assistant, Joseph B. Lancaster, and pay him from his own salary. Lancaster, resigned on December 8, and Lewis Huguon was appointed in his place. After adjudication began the services of the secretary were necessary to record the evidence of titles and the commissioners were compelled to pay the salary of a second assistant, John M. Lawrence, to take the minutes. The number of claims was too great for the commissioners to dispose of them in the time allowed, under the conditions stipulated in the law, there being something like 600 by February 21, 1824. Property owners in St. Augustine and Fernandina were disgruntled because they were required to exhibit their titles, Section II of the treaty seeming to imply that all private claims in those towns were accepted as valid, only the public property being transferred to the United States. They accordingly held mass meetings and petitioned Congress to exempt them from the necessity of exhibiting their titles, and the Board agreed to submit the question to the Secretary of the Treasury. No reply had been received at the end of the year and the claims had not been considered.

The Board had other troubles which prevented its functioning smoothly. It moved its offices twice—from Government House to a house belonging to Joseph Sanchez, then back to Government House. It was unable to obtain certain documents from the Public Archives and was compelled to issue a subpoena duces tecum to William Reynolds.

The same procedure was necessary even after the Secretary of State instructed him to deliver the documents. And finally there was such a divergence of opinion between Hamilton and the other commissioners as to procedure that Hamilton refused to participate in the sessions and bombarded President Monroe, Secretary of Treasury Crawford, Secretary of State Adams, and the chairman of the house committee on public lands with serious charges against his colleagues and those in charge of the Public Archives. After Hamilton ceased to participate the two commissioners adopted the rule that in cases of disagreement between them the claims with all the facts should be reported to Congress for disposition.

As former United States district attorney for East Florida, Hamilton was on the ground when he was appointed to the Board, and on June 7, before the other commissioners arrived, he appointed a secretary, Peter Lynch, to receive land clams. When the organized on August 4, it dispensed with Hamilton's appointee, chose Fatio secretary, and ordered all papers that had been filed returned to claimants "to be presented in proper order."

Whether or not friction was first caused by Hamilton's officiousness in beginning the work before the Board had organized and inserted in the newspapers the necessary instructions to claimants, the minutes show that there was seldom agreement between Hamilton and his colleagues. He complained of "the important and procrastinated situation of the business of the commission," or the failure of the Board, as he saw it, to adopt certain principles to govern their decisions, and of the "illegal and improper manner in which the Minutes were kept on loose sheets." On December 9 the Board ordered the secretary to record the minutes in a "well-bound book," as the law required.

The Act creating the Board for East Florida had not defined "actual settlers." The majority of the Board defined the term as meaning persons actually settled within the province at the time of the exchange of flags but not necessarily on the land claimed. Hamilton did not agree with the definition (and neither did Congress, for the following year, in an Act to extend the time for the settlement of private land claims in Florida, it defined actual settlers as those who were in the cultivation or occupation of the land at or before the date of cession.

The more serious charges made by Hamilton were in regard to 1. the careless and haphazard manner in which he said the public archives were kept, which had resulted in one or more documents being altered, one stolen and another substituted, and the dependence of the Board on such an office for transcripts or certified copies instead of insisting upon the original documents; and 2. fraud in connection with the favorable action of the Board on McIntosh, Segui, and Arredondo claims. Hamilton was skeptical of the testimony of George J.F. Clarke, surveyor-general under the Spanish government, and of his "pretended deputy, Burgevin," the latter of whom he characterized as "contemptible." He commented on Clarke's "extravagant pretensions and inconsistent representations, with a memory on some subjects singularly tenacious, and on others peculiarly forgetful." Hamilton resigned on March 31, 1824, but a month later withdrew his resignation until the end of the session of Congress that his communication might in the meantime "have official importance." The committee on public lands did not sustain Hamilton, but it recommended that the President give the Board instructions as to its powers and duties and adopt such measures as were necessary for the safe-keeping of the archives.

At the end of the year the Board reported to Congress the principles Hamilton stated to the Secretary of the Treasury that he would go from St. Augustine to Charleston and there hold himself in readiness should his presence be required in Washington in connection with his charges. An aftermath of Hamilton's sojourn in Florida was three court cases. Two of the cases, filed Feb. 9, 1824, were for libel in the sums of $10,000 and $20,000 in connection with his alleged candidacy for territorial delegate to Congress and a petition to the president signed by a number of persons for his removal as a member of the Board of Land Commissioners. —Alexander Hamilton v. Eusebio Gomez and Alexander Hamilton v. Eusebio Gomez and Joseph H. Hernandez, File H 3, Superior Court, St. Johns County, Fla. In the third case Hamilton brought suit for damages in the sum of $1,600 against the master and commander of the sloop "Rapid" for loss of his trunk and law books when the sloop burned at Charleston wharf on July 6, 1824. — Alexander Hamilton v. Alexander G. Swasey, File H 10, Superior Court, St. Johns County, Fla. upon which it had based its decisions: 1. the aw of the Indies; 2. royal orders; 3. decrees and regulations made and published by the local governors; and 4. customs and usages which prevailed in the various offices of the territorial [Spanish] government. Another principle upon which they acted was acceptance of royal titles granted without conditions and of those granted after January 24, 1818, provided the latter's conditions were fulfilled before that date.

Early the following year Congress increased the work of the commissioners by adding another class of claimants. There was in the Territory of Florida a large number of settlers who had no titles to show for the lands they occupied—renters, squatters, or purchases of lands with doubtful titles. The majority of these were probably citizens of the United States. To retain and do justice to these settlers Congress by the "Donation Act" of May 26, 1824, authorized the commissioners "to receive and examine all claims founded on habitation and cultivation of any tract of land, town or city lot or outlet by any person being head of a family and 21 yeas of age," who on February 22, 1819, the date of the signing of the treaty, "actually inhabited and cultivated such tract of land, or actually cultivated and improved such lot, or who, on that day, cultivated any tract of land in the vicinity of any town or city, having a permanent residence in such town or city." To such persons they were to grant certificates of confirmation not to exceed 640 acres.

The Act provided also that the commissioners were to receive claims to land founded on habitation and cultivation commenced between February 22, 1819, and July 17, 1821, the date of the abstract of all such claims to the Secretary of the Treasury. Claims merely reported upon were to be laid before Congress "with the evidence of the time, nature and extent of such inhabitation and cultivation…and extent of the claim," but no claim was to be received, confirmed, or reported in favor of any person who claimed any tract by virtue of any written evidence of Title from either the British or Spanish governments.

Davis Floyd and William W. Blaire, commissioners for East Florida, met on March 29, 1824, pursuant to the law of the February 19 which extended the time limits for the settlement of private land claims in East Florida to January 1, 1825. Congress having failed to make an appropriation for employing assistant clerks, the services of the minuting secretary and the messenger were discontinued. Through April to August the Board had often to adjourn for lack of a quorum, due to Blair's illness. On August 24 George Murray, who had been appointed "vice for William W. Blair", was present for the first time; and on September 29 William Henry Allen, who had been appointed on August 12 as the third member of the Board, was in attendance.

On December 28 the Board adjourned sine die. In its report, dated January 1, 1825, the Board stated that it had found it impossible to complete the work within the time specified by law. The Commissioners explained that property had often been conveyed one, two, three, or even four times and petitioners had frequently received grants at certain places, changed their minds and had surveys made elsewhere, which made the examination of claims exceedingly tedious. They had employed an additional clerk [probably Thomas Murphy] for the past three months who so far had revived no pay, and he had been able within that time to record only 34 claims, since they averaged 21 pages each. There were 1,104 claims filed during the year, of which 80 were still under advisement.

On March 3, 1825, an Act of Congress extended the time of the commissioners for East Florida to the first Monday in January, 1826, and made appropriations for two additional clerks.

The Board in West Florida having in large part completed its work, the Act directed the commissioners there to deliver all records and evidence relative to land claims to the Register and Receiver of the Land Office in West Florida, who should examine and decide the remaining claims subject to the rules which had governed the commissioners.

On March 28 the Board for East Florida met with Davis Floyd, George Murray, and William H. Allen, commissioners, and Francisco Jose Fatio, secretary, present. Thomas Murphy and Lewis Huguon were appointed assistant clerks. (134) Sessions were held in Jacksonville on May 16 and several times thereafter for the convenience of claimants. It adjourned sine die on December 30, 1825. Its reports of January 1 and 31, 1826, showed more than 500 claims yet undetermined. The Board was criticized in the press, being charged with allowing counsel to appear for claimants and for itself with the object of killing time and prolonging its life. Floyd made a spirited defense to the Secretary of the Treasury and related the difficulties under which the commissioners had labored. He charged that doubtful claims had been held back by their owners and criticisms against the Board made in the hope that "the business might fall into more favorable hands."

There is no doubt that the commissioners for East Florida had a far greater task than did those for West Florida. The number of claims in East Florida was greater, the claims were more complicated and it may have been that the commissioners were less systematic in handling them. It would seem also that friction among themselves retarded the work. The remaining claims were disposed of by the Register and Receiver of the Land Office for East Florida. (139) Charles Downing and William H. Allen.

By Act of Congress on February 8, 1827, the "secretary of the late commissioner" for East Florida was directed to deliver all land papers in his possession to the Register and Receiver of the Land Office for East Florida who should examine and decide the remaining claims subject to the several laws on Congress. Claimants were directed to file their claims before November 2 and the Register and Receiver to report on January 1, 1828. Conflicting claims were to be subject to court decision. Holders of claims of more than 3,500 acres and other claims not yet reported by commissioners, or by Register and Receiver, were to furnish to the surveyor within one year the information concerning their claims so that he might connect them with the township plats then under survey. (140)

On May 23 of the following year Congress enacted a law limiting to one league square the amount of land which might be confirmed in any one claim. (141) The Register and Receiver were directed to continue to examine and decide the remaining claims in East Florida until the first Monday in December, 1828, after which it would be unlawful for any claimant to exhibit any evidence in support of a claim.

Spanish claims not settled before that date, containing a greater amount of land than the commissioners were authorized to decide, and which had not been reported as antedated by the commissioners or the Registers and Receivers, were to be adjudicated by the judge of the superior court of the district within which the land lay, upon petition of the claimant, under restrictions prescribed to the district judge. The judge was not to take cognizance of any claims annulled by the treaty not any claim presented to the commissioners or to Registers and Receiver. Claimants were to be permitted to take an appeal from the superior court to the Supreme Court of the United States within four months after the decision, Claims which exceeded one league square and all other cases in which the United States district attorney thought the superior court had erred were to be appealed. Claims were to be brought before the court by petition within one year and prosecuted to a final decision within two years or be forever barred both by law and equity, but decrees so rendered were to be conclusive between the United States and claimant only and were not to affect the interest of third persons.

The question of certain claims which the Spanish government had confirmed subsequent to January 24, 1818, and which the commissioners had reported favorably to Congress, had not been passed upon by that body. On May 26, 1830, a law was passed providing that these claims should be re-examined and reported by the Register and Receiver before the next session of Congress. The act further provided that all remaining claims which had been resented according to law and not finally acted upon were to be adjudicated as prescribed in the act of May 23, 1828. All confirmations of land titles were to operate only as a relinquishment of the right of the United States and were not to be construed either as a guarantee of such titles or in any manner affect the rights of other persons to the same lands. Those who availed themselves of the opportunity to take one league square in lieu of the whole grant were allowed one year in which to execute their relinquishment.

Legislation respecting the settlement of Spanish land claims was now ended. Henceforth cases were settled in the courts. When Florida attained statehood in 1845 it abolished the superior court and transferred its former territorial jurisdiction to the state circuit courts. By the act of February 22, 1847, Congress transferred the Federal jurisdiction which the court had exercised to the newly created district court of the United States for the District of Florida, and land cases pending in the superior courts were transferred to it.

In February, 1835, the House of Representatives asked for a detailed report on claims pending in the courts under the Act of 1828 and on those confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court, together with an opinion as to whether the pending cases come within the provisions of those already decided by the court. The report, made in the following December by Richard Keith Call, Receiver at Tallahassee and counsel for the United States in the settlement of claims, shows:

No. 1—Abstract of mill grants 20 in number

No. 2—Abstract of grants "alleged to have been made

For services rendered the Spanish government" 19 " "

No. 3—Abstract for claims under grants made on

Condition of habitation and cultivation 4 " "

No. 4—Abstract of miscellaneous cases 16 " "

Pending in superior Court of East Florida at St. Augustine 60 " "

Petitions filed but not yet placed on docket 18 " "

Pending in Superior Court of East Florida at Jacksonville 14" "

Appeals made to the U.S. Supreme Court from decisions against the government rendered in the

Southern Judicial District 2 in number

Pending in Western and Middle Districts 1 " "

Call was of the opinion that three of the mill grants might be confirmed in line with the case of Francisco Richard (U.S. v. Richard, 8 Peters, 470) who had built a mill and so fulfilled the condition. In his discussion of group No. 2, Call said that under the careful scrutiny of the commissioners these claims had been abandoned, but under the law of 1828 they again "sprang up" and while the Register and Receiver did not positively declare them forgeries and so exclude them from the courts under the law of 1828, it was evident that they regarded the claims as fraudulent. He was critical of the Supreme Court's favorable decision in the case of Mitchell et al v. United States (9 Peters 711) in which he said the court accepted as authentic documents which were "copies of copies", none of which were executed by a notary public and authenticated under his official seal. He thought the "badges of fraud" were as strongly developed in that case as in any of the pending cases, and if the latter were to be decided according to the principles laid down in the Mitchell case, then all the pending cases against the government would be confirmed.

There were numerous reasons why certain land grants in Florida were not confirmed; some of the less obvious reasons are given below.

Often claimants had not filed within the prescribed time, which expired November 1, 1827. One such person was Antonio Pania (Pancia?) (146) who the Board remarks had according to witnesses fulfilled every requirement for a donation grant and had cultivated the place for 12 or 15 years, but filed his claim in September, 1828. The same was true of John Hall, (148) of whom the commissioners' decree said "…if his claim had been filed in time we would confirm it; but it was presented to this Board in September, 1828."

Sometimes there was a suspicion of fraud. Of one such claim the commissioners said, "…This paper is filed in the office of the archives, where it originally should have been, if the claim is genuine. The paper presented to us is claimed to be the original, and proof of the signature of Kindelan was tendered to this Board, but not received." The Board noted also that the land lay within the Indian boundary in which grants were almost never made by Spanish governors, but "above all, the grant is dated on the 15th May, 1815, by authority of a royal order of 29th of March preceding, which was transmitted from Madrid by way of Havana, and communicated to the governor of this place by the captain-general, Apodaca, by a letter bearing the date of 7th July, 1815, nearly two months after the date of the grant…"

The grants of Governor Coppinger and the surveys of George J.F. Clarke shortly before the cession were looked at askance. Although instructions to the surveyor-general directed him "when called on by any person to measure and bound lands…to require his title of property or grant from the government…," and to keep regular books in which his surveys were to be recorded, he testified before the commissioners that he possessed authority to survey without a special order, that he located wherever the claimant pointed out, that he kept no regular books of survey after the summer of 1817, and that he did not consider the governor's order obligatory.Clarke issued a number of certificates of survey, alleging "disposition of S.S. (Su Senoria, His Excellency) of October 20, 1817," for which no authorization from the governor could be found.

Often conditions had not been fulfilled. Both British and Spanish grants as a rule carried conditions with respect to occupation and cultivation, the number of acres which should be cleared or drained within a given period, the number of cattle that should be pastured, or the establishment of a saw or grist mill, and the treaty permitted the same length of time for such conditions to be fulfilled in the event circumstances had previously prevented their fulfillment. (Many who presented

claims had made no effort either under the Spanish government or under that of the United States to fulfill the conditions of their grants.

Sometimes royal titles were granted after January 24, 1818, when there was no evidence of occupation or even a conditional grant previous to that date. For example, Joseph M.. Hernandez received a grant on April 6, 1818, and two days later a title in absolute property.

Often the surveys were not in agreement with the terms of the grants. The Supreme Court held that surveys to have validity must have been in conformity with the grants on which they were founded.

Certificates issued by Thomas Aguilar as Spanish government secretary were questioned by the board, particularly by Alexander Hamilton, and later by government counsel in cases before the courts. Here the Board was not sustained, the Supreme Court deciding in several cases that Aguilar's certificates were valid evidence

Sometimes surveys had been made and certified only by private surveyors, the claimant offering no other evidence. The Supreme Court held that the certificate of a private surveyor purporting to show that he had permission from the governor to make a survey was no evidence of the fact, but that plats and certificates of the surveyor-general, because of his official capacity, should be given the credence that would have been accorded them by the Spanish government.

There remain to be mentioned those British claims for lands which British subjects were unable to dispose of at the time of the retrocession of the province to Spain in 1783. They were brought forward after the cession of Florida to the United States, but were not confirmed by the Boards of Commissioners or by Congress. Even William Drayton's claims failed of confirmation, although his difficulties with Governor Tonyn, which resulted among other things in the loss of his position as chief justice of East Florida, were in large part due to his sympathy for the patriot cause in the American Revolution. The law of Congress under which the Board was organized in 1822 instructed the commissioners 1. to ascertain how far the British claims were valid under the law of nations and 2. how far they had been considered valid under the Spanish government if satisfied of their validity, the claims were to be confirmed.

English claimants did not pretend that their claims were valid under the Spanish government, but endeavored to avail themselves of the jus postliminium as laid down in Vattel and other writers on international law, by means of which person and things taken by the enemy might be restored. Overton and White, in their report of January 20, 1825, on the British claims went into the subject thoroughly, showing that according to Vattel the principle which the British invoked could only have been made to operate in favor of British claimants had Florida been restored to England rather than sold to the United States, which was not a party to the war between Great Britain and Spain In addition, the treaty of 1783 between Great Britain and Spain recognized the claims by providing that subjects of the former should have eighteen months in which to dispose of them.

Furthermore, the commissioners expressed the opinion that had these claims been presented to the Spanish government before the cession of Florida to the United States, Spain would have pronounced them null and void. That the claims were not presented was evidence in their judgment that the English themselves thought so.

The commissioners pointed out also that the conditions of the English grants were not fulfilled under the Spanish government and quoted Blackstone as authority for this fact alone as being evidence that the claims were at least voidable. They expressed the opinion that even under English law the claims would not be recognized. Spain regranted the lands claimed by those British subjects who left their lands in Florida after 1783 and "if Spain could regrant them and sell them at public auction, the United States, as the successor of Spain, are entitled to all the advantages resulting from a similar disposition of the property." They concluded that the British grants which were not confirmed by Spain are "forfeited, void, and of none effect.

Louise Biles Hill - Manuscripts Editor Entire document and all references can be seen at floridamemory.com

Back to Index

Unfortunately, most of the records for West Florida are missing.

What do the records tell us? The grants provide information on the settlement and cultivation of Florida during the Second Spanish Period (1783-1821) and the Territorial Period (1821-1845). Grantees had to provide the following information: description of land granted; date of grant; size of grant; property boundaries; and proof of residency and cultivation. Therefore the records contain surveys and plats, copies of royal grants, testimonials; correspondence, deeds, wills, and translations of Spanish documents. A note of caution: because many of the grants conflict and overlap with each other, not all of the information in the records can be considered accurate. Some of the surveys were not verified on the ground, nor was there a complete survey for Florida until the late 1820s. Serious researchers should also consult other land collections (see Related Resources).

An interesting paper written on the subject:

The Impact of Spanish Land Grants on the Development of Florida and the South Eastern United States by Dr. Joe KNETSCH, USA

ABSTRACT - The paper discusses the development of Florida and the Southeastern United States in light of the numerous and confusing system of Spanish Land Grants. The author argues that the development of Florida, and parts of the Southeastern United States, may have developed at a more rapid pace if the confusion caused by conflicting land claims had not interfered. It is shown that land grants given to British officers and favorites caused concern with land title validity on the early frontier. Spanish co-option of these claims further increased the confusion of title and acted as an inhibitor to settlement. Greater problems arose from the fraudulent claims and liberal interpretation given the powers of the Surveyors General, especially in East Florida. The acceptance of fraudulent evidence in West Florida and the

Florida Parishes of Louisiana indicated some corruption of early American officials that also retarded settlement. The final, and most important, cause of slower settlement of these areas was the problem of grant location by the United States Deputy Surveyors. Until these grants were properly located and laid out, few Federal surveys could be conducted. Without proper survey lines and the tying in of the land grants to the rectangular system, no safe title could

be given out. This lack of certain title to land acted as a blockage to a more rapid development and settlement on the Southeastern frontier of the United States, especially in Florida. View Document in it's entirety at www.fig.net

Another interesting paper on the subject:

Negotiating the Maze: Tracing Historical Title Claims in Spanish Land Grants . . .

by Sidney F. Ansbacher and Dr.Joe Knetsch

V. BACKGROUND OF SPANISH LAND GRANTS

Spain ruled Florida through civil law. The Florida Supreme Court discussed the Spanish colonial law as to waterfront lands at length in Apalachicola Land & Development Co. v. McRae: When Spain acquired territory by discovery or conquest in North America, the possessions were vested in the crown; and grants or concessions of portions thereof were made according to the will of the monarch. While the civil law was the recognized jurisprudence of Spain and its rules were generally observed, yet the crown could exercise its own discretion with reference to its possessions.

Under the civil law in force in Spain and in its provinces, when not superseded or modified by ordinances affecting the provinces or by edict of the crown the public navigable waters and submerged and tide lands in the provinces were held in dominion by the crown . . . and sales and grants of such lands to individuals were contrary to the general laws and customs of the realm.

"By the laws and usages of Spain the rights of a subject or of other private ownership in lands bounded on navigable waters derived from the crown extended

only to high-water mark, unless otherwise specified by an express grant."

This decision was recently re-examined and reconfirmed in the First District Court of Appeal in Florida in Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund v. Webb.

As the McRae court noted, Great Britain divided Florida into East and West Florida during British occupancy from 1763 to 1783.82 The Chatahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers split East from West Florida. Spain retained the East/West split when Florida reverted from Great Britain to Spain in 1783. Florida became subject to United States law under the cession from Spain to the United States, effective in July, 1821. The Treaty of Amity, Settlement and Limits Between